Ned Kelly and his Dad - John Red Kelly

Written by

Matty Tynan in association with Siobhan O’ Neill

in Australia.

The story of Ned Kelly, Australia's last and most famous bushranger, had its real beginnings in Ireland.

His father, John Kelly (nicknamed 'Red') was born and reared in the townland of Clongbrogan, just outside Moyglass.

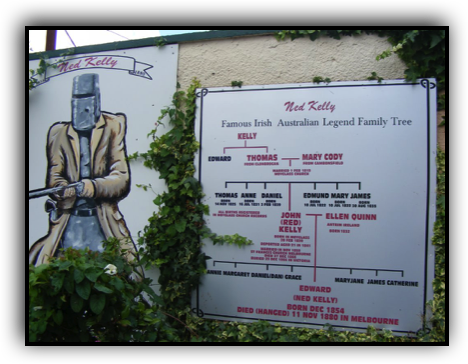

Young John Kelly was baptised in Moyglass Church on 20th February 1820, the same church where his father Thomas was married to Mary Cody on 1st February 1819, when Thomas was just 18 years of age. Thomas Kelly’s parents, John Kelly and Ellen Head, were also married in Moyglass on 16th June 1799.

John Kelly was the eldest of seven siblings, four brothers and two sisters, and all except one (Thomas junior) were to travel to far off Australia; five through emigration and one, John, by other means.

On 4th January 1840, 20 year old John Kelly was convicted of stealing two pigs, “value about six pounds” from a neighbouring farmer named Cooney. He was kept in Mobarnon Police Station until 7th January 1841 when he appeared at Cashel and was sentenced to seven years' transportation to Australia.

It was 31st July 1841 when John Kelly was finally brought to Dublin port and placed aboard the convict ship the Prince Regent. The ship set sail for Van Diemen's Land, now Tasmania, on 7th August with only one stop, in Cape Town, and arrived on 2nd January 1842.

Despite the infamous brutality of the penitentiary at Port Arthur, John Red Kelly proved himself to be a model prisoner and was released in 1848, with six months cut from his sentence for good behaviour. Most convicts released from Port Arthur made their way across Bass Strait to the Port Phillip District (now Victoria). Red Kelly was no exception and, landing in Victoria, he immediately made his way northward to a strong Irish community at Wallan Wallan, north of Melbourne.

Red Kelly, a quiet and unassuming man, was now 31 years of age. He found work as a bush carpenter and, while working at the farm of his neighbour James Quinn, he fell in love with James' eldest daughter, 18 year old Ellen (Nelly) Quinn. The Quinns had emigrated from Ballymena, County Antrim. The match was not favoured by James Quinn, so the couple eloped on horseback to Melbourne, where they were married on 18th November 1850 in St Francis' Church by Fr. Gerald Ward.

The young couple tried their luck on the goldfields, where they didn't strike it rich but they did make enough money to buy a farm in Beveridge, a small hamlet not far from Wallan, on the main Melbourne to Sydney road. Their first child, Mary Jane, was born in 1851 but died in infancy. In the following years, they welcomed to the world Annie, Maggie, Edward (Ned) around June 1855 (his birth was not registered), then Jim, Dan and Kate.

John Red Kelly worked his farm and sold provisions to the hopefuls who tramped to the goldfields of central and north east Victoria.

In 1864 the Kellys moved further north to Avenel, where their last child, Grace, was born in 1866; Red Kelly registering her birth at the village store, identifying himself as the father, “John Kelly from Moyglass, Tipperary, Ireland”.

The family were poor, but happy, and the children all did well at school. When Ned was 10 years old, he bravely saved the life of young Richard (Dick) Shelton when the younger boy fell into Hughes Creek and nearly drowned. Dick Shelton's parents, who owned the Royal Hotel in Avenel, were so appreciative that they presented young Ned with a magnificent emerald green sash with a gold bullion fringe. Ned was found to be wearing it 15 years later at his famous Last Stand in Glenrowan.

In early 1866, a wealthy local farmer reported that a calf was missing. Although it was 13 years since Red Kelly was released and he hadn't been in any trouble in all that time, the stigma of being an old “lag” was hard to shake and police called on the Kelly home. Finding meat in the cooler and a calf hide tanning outside, they arrested Red Kelly. Protesting that the meat and calf hide were from his own stock, John Red Kelly was nevertheless found guilty and sentenced to six months hard labour.

Ellen, then pregnant with Grace, was unable to raise the 25-Pounds bail, and John served his time but came out of prison a broken man. Diagnosed with dropsy, he died on 27th December 1866 at the age of 46, and was buried in Avenel Cemetery.

Young Ned was just 11 when his father died and he had the onerous task of recording his father's death at the village store, proudly signing his full name, Edward Kelly, in the register. For the rest of his life, Ned would call himself “Ned Kelly, son of Red Kelly, and a better man never wore boots!” Leaving school, Ned Kelly assumed the role of head of his family, and became his mother's greatest support.

James Quinn had done well in Australia, and had moved his family to a selection called Glenmore, some 200kms away in North East Victoria. In an effort to be closer to her family, Ellen made the heartbreaking decision to leave Avenel, where they had all been so happy together. Ned helped his mother load-up their wagon and they started on a journey that took several days over rough roads, camping by the road or in fields along the way.

They settled in Greta, where Ellen found work as a domestic, laundress, and seamstress. Ned, a strong youth, quickly found work chopping and carting wood. By 1869 they had saved enough money for Ellen to qualify for a selection of 88 acres on the banks of the Eleven Mile Creek just out of Greta. They supplemented their income by distilling and selling ‘sly grog’ (illegal alcohol), and providing accommodation for passing carriers, hawkers, seasonal workers and travellers.

Although the Quinns had never been in trouble with the law in Ireland, Ellen's brothers grew into wild men who drank and brawled and were involved in horse and cattle duffing. Two of Ellen's sister married the Lloyd brothers and the Quinns, Kellys and Lloyds were soon to become the focus of police attention.

When Ned was fourteen years old, his Lloyd cousins suggested to Ellen and Ned that he could make money helping Harry Power; an Irishman who bailed up coaches and travellers with legendary gallantry and joviality. Young Ned had the job of holding Harry's horse when he was “working”, but a close call in which they were both nearly shot by a wealthy landowner was enough to force Ned to hand-over the reins. Harry Power was arrested by police who crept up on his hideout while he was asleep. Harry Power always blamed Ned Kelly for informing on him, but it was his uncle Thomas Lloyd who actually led police to the old bushranger's hideout high above the Glenmore property.

In the same year, Ned Kelly was arrested for assault on a Chinese worker, who had called at the Kelly property asking for a drink of water. When Maggie gave him creek water, the man apparently became angry and started yelling and brandishing a stick at her. Ned was working in the field and came to his sister's assistance, taking the stick from the man and chasing him from the property. The case was dismissed.

However, in 1870, Ned was charged with assault on a local hawker named McCormick. Ned claims that when he returned McCormick's horse, after finding it broken loose and wandering near the Kelly farm, McCormick accused Ned Kelly of using his horse to pull a rival hawker from a bog. Ned Kelly claimed the hawker threatened to thrash him, so the 15 year old obliged and started to dismount from his horse. Mrs. McCormick, realising her husband would not get the better of a round, jumped to stop them and Ned Kelly's horse spooked, leaping forward and knocking McCormick to the ground. He received a sentence of three months.

Ned was only out of prison three weeks when a friend of the family, Isaiah “Wild” Wright visited and put his horse in the Kelly paddock. When the horse broke out, Wright borrowed the horse of Alec Gunn, a young Scot who had married Annie Kelly, saying he would collect his horse when he returned. When Ned Kelly found the horse, he openly rode it in and out of Greta and nearby regional town Wangaratta. He had been doing so for a couple of weeks, even giving the pub owners daughters rides up and down the main street, when the local policeman decided to check the horse against the Police register. It appeared as stolen from the postmaster at Mansfield, some 50kms away. He called Ned Kelly to the gaol, on the pretence of signing some papers to do with his release, but jumped on the unsuspecting youth and tried to arrest him. Ned Kelly fought with the policeman and quickly overcame him. Constable Hall called for help from onlookers and eight men were eventually needed to subdue the youth. Once he was restrained, the policeman hit Ned Kelly over the head with his (Hall's) revolver. Mrs. Kelly and Wild Wright followed the blood trail to the barracks, where a local doctor inserted eight stitches in the 16 year old's scalp. Ned Kelly, Wild Wright and Alec Gunn were all brought before the court and Wild Wright was sentenced to 18 months with hard labour for stealing a horse.

Although Wright had testified that neither Kelly nor Gunn had known the horse was stolen, both were charged with receiving stolen property and received an astonishing sentence of three years' hard labour.

While Ned Kelly was in prison, a young American named George King came to the Greta area. Having tried his luck on the goldfields in both America and Australia, he asked to do jobs for board. George was 25 and the widow Kelly was 42, but somehow they fell in love and George proposed, but Ellen decided to wait until Ned's release and, hopefully, approval.

It is unknown what Ned Kelly felt about the union but, always devoted to his mother, her happiness would be paramount, and he appeared as a witness in his 19th year, signing his name in the church register while the bride and groom signed with the common cross-mark of the 19th century's semi-literate.

Ned Kelly gained work in a local sawmills and quickly rose to the role of overseer. Well paid in his job, he stayed out of trouble for three years. An excellent marksman, horseman and builder (he had built a new home for his mother on the Eleven Mile Creek and a big sandstone house for a farmer in nearby Winton), he was an athletic man, and tall in his time standing at nearly six feet. He also won a gruelling 20-round bare knuckle boxing match against Wild Wright in the goldmining town of Beechworth, making him the unofficial boxing champion of North East Victoria.

When the sawmills closed, Ned made the fateful decision not to follow it to Gippsland where it was opening again. Instead, he invested his savings into gold panning expeditions with George King.

However, when they were unsuccessful, Ned Kelly surrendered to the lucrative trade of what he called “wholesale and retail horse and cattle dealing”; i.e. horse and cattle duffing. Top horseflesh was stolen from wealthy landowners, known as the “squattocracy”; they were squatters who had built great wealth and power.

In 1878, life was to deal another cruel blow to the Kelly family when trooper Alexander Fitzpatrick came to the Kelly home to question Dan about some stolen horses in the nearby town of Chiltern. Dan asked to be allowed to finish his dinner and the policeman agreed. Constable Fitzpatrick had already set an appreciative eye at 14 year old Kate Kelly and, according to the family, when he was inside the hut he pulled young Kate on to his knee. Outraged, her mother ordered him from the home, but Fitzpatrick pulled his gun saying it was his authority to stay. Mrs. Kelly said that if her son Ned were there Fitzpatrick would not be so brave. The sound of approaching footsteps caused the policeman to jump to action and Dan took this opportunity of clapping Heenan's Hug on the trooper. They struggled and fell, Fitzpatrick denting his helmet when he landed and catching his wrist on a latch. The family say they patched the policeman's flesh wound and he remained at the house for several more hours. They say Fitzpatrick assured them he was fine and there was no problem, though he advised Dan to “clear into the bush and let it all blow over”.

The policeman's story, however, was much different. He claims that when he entered the hut, Mrs. Kelly hit him over the head with a shovel (no exact reason ever given) and Ned Kelly came in the door firing three shots at the policeman, only hitting him in the wrist with the third shot. It should be noted that Fitzpatrick disobeyed an order that no police were to go to the Kelly home alone, and he had been seen to stop at drinking houses on the way to and from the Kelly home.

Irrespective, police swooped on the Kelly home and arrested Ellen Kelly, her son-in-law Bill Skillion (who had married Maggie Kelly) and neighbour Bricky Williamson for the attempted murder of a policeman. Ned and Dan Kelly were wanted for questioning.

They appeared before Justice Redmond Barry, the Irish born son of English landed gentry in Cork. A brilliant lawyer, Redmond Barry was known as the Hanging Judge because of his penchant for giving harsh sentences for menial offences. He was feared on the goldfields, where he heard many cases, and was often surrounded by controversy over his private life; never married, he was said to have fathered 16 children. But he worked tirelessly to make Melbourne a place of culture and learning, acquiring thousands of acres to establish the University of Melbourne, State Library, and many other buildings and services promoting the arts. He apparently donated services to aboriginal cases and was so committed to education and learning, that he even opened his own extensive library to members of the public before library services became available.

In October 1878, Ellen Kelly King, with a new baby in her arms, appeared before Justice Barry at Beechworth Court. She was sentenced to three years hard labour for attempting to murder a policeman, while Bill Skillion and Bricky Williamson were each sentenced to six years hard labour. Although Ned and Dan Kelly were only wanted for questioning, Justice Barry told Ellen: “If your son Ned were here I would make an example of him, I would sentence him to 15 years”.

Ned Kelly always denied that he was present at the Fitzpatrick incident, admitting instead that he was horse and cattle stealing interstate at the time. On news of his mother's imprisonment, he was outraged and wrote:

“Fitzpatrick is the meanest article that ever the sun shone on. The jury thought it impossible for a policeman to swear a lie, but I can assure them it is by that means, and by hiring cads, that they get promoted. He can be thankful I was not at home when he took a revolver and threatened to shoot my mother in her own home. I heard nothing of this transaction until later, as I was over 400 miles away from Greta, when I heard that I was wanted for shooting at a trooper in Victoria. It is not likely that I would fire three shots at Fitzpatrick and miss him at a yard-and-a-half. I don't think I would use a revolver to shoot a man like him, when I was within a yard-and-a-half of him, or attempt to fire into a house where my mother, brother and sisters were, according to Fitzpatrick statement, 'all around him'. A man who is such a bad shot as to miss a man three times at a yard-and-a-half would never attempt to fire into a house full of women and children. I would not do so while I had a pair of arms and a bunch of fives at the end of them that never failed to peg-out anything they came into contact with. Fitzpatrick knew the weight of one of them only too well, as it ran against him once in Benalla and cost me two-pound-odd, as he is very subject to fainting”.

Ned Kelly found his brother Dan camped in the dense ranges outside Mansfield. Dan was gold panning and distilling poteen. He'd been joined by his mate Steve Hart from Wangaratta and Ned's mate Joe Byrne from Beechworth; both were also sons of poor Irish farming families. The Kelly brothers wanted to surrender themselves and ask for the release of their mother and friends, but Joe and Steve persuaded them this was useless. None expected justice.

The Fitzpatrick Incident, as it became known, sparked a vigorous police hunt for the Kelly brothers. In October 1878, a party of four was dispatched from Mansfield to cross the ranges and meet with another party coming from the other direction. The Mansfield party were all Irish-born, led by Sergeant Michael Kennedy of Westmeath, it also comprised constables Michael Scanlon from Kerry, Thomas Lonigan of Sligo and Thomas McIntyre from Belfast. They were dressed as prospectors, but were heavily armed and their horses carried ominous straps generally used for transporting bodies. They camped on the banks of Stringybark Creek, not a mile from the Kelly hideout.

On 26 October 1878, the four youths approached the police camp, where Lonigan and McIntyre had remained while Kennedy and Scanlon went scouting. They were lazing by the fire when a voice suddenly called, “Bail up! Throw up your arms”. McIntyre was unarmed and immediately surrendered, but Lonigan dropped behind the log and, aiming his gun, was shot dead by Ned Kelly. Assured by the gang that no man who surrendered would be shot, McIntyre agreed to ask the other police to surrender when they returned to camp. Later that afternoon, they could be heard approaching and McIntyre approached them saying, “You'd better throw down your arms, we're surrounded”.

Thinking it a joke they laughed, until Scanlon caught sight of Ned Kelly, slung his rifle and fired. Ned Kelly shot and Scanlon fell dead from his horse. Kennedy jumped on the offside of his horse and ran into the bush for cover. McIntyre took advantage of the confusion to jump on Scanlon's horse and gallop for help. Ned Kelly pursued Michael Kennedy into the bush and engaged in a gun battle that resulted in the sergeant's death. In a mark of respect, Ned Kelly covered the policeman's body with his cloak. McIntyre, racing in hysteria through the dense bush, fell from his horse and, fearing the Kellys might be chasing him, hunkered down for the night. In his diary he wrote: “Ned Kelly, Dan and two others stuck us up while we were unarmed. Lonigan and Scanlon are shot. I am hiding in a wombat hole until dark. The Lord have mercy on me. Scanlon tried to get his gun out”.

Thomas McIntyre reached Mansfield the next day and delivered the shocking news of the massacre. He led a police party the following day to retrieve the bodies of constables Scanlon and Lonigan. Michael Kennedy's body was not found for several days.

The police were buried with full honours and an impressive monument to their memory was erected in the centre of Mansfield.

Of the Stringybark Creek battle Ned Kelly later wrote:

“I could not help shooting them, or else let them shoot me, which they would have done if their bullets had been directed as they intended. After Kennedy was shot, I put his cloak over him and left him as well as I could. If they had been my own brothers, I could not have been more sorry for them. This cannot be called wilful murder, for I was compelled to shoot them or lie down and let them shoot me. It would not have been wilful murder if they had packed our remains in, shattered into a mess of gore, to Mansfield. They would have got great praise, as well as promotion, but I am reckoned a horrid brute because I was not cowardly enough to lie down for them, under such insults to my people. Certainly their wives and children are to be pitied, but those men came into the bush with the intentions of scattering pieces of me and my brother all over the bush. Yet they know and acknowledge that I have been wronged, and my mother and four or five men lagged innocent. And is my mother and brothers and sisters not to be pitied also?”

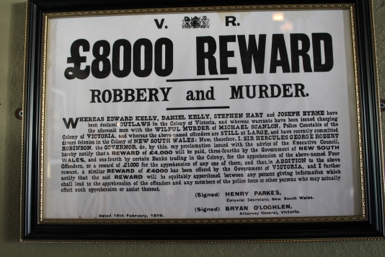

The Government immediately instituted an Act of Outlawry and set a reward of 400-Pounds for Edward and Daniel Kelly and two unknowns.

By the end of 1878 they needed money and, in his practical thinking, Ned Kelly decided they must rob a bank. They chose the National Bank at Euroa, a sleepy farming town on the main Melbourne to Sydney road. Arriving at Younghusband's Faithfull Creek property just out of town, they set-up base and detained workers and anyone who happened along, keeping the men in a large storeroom, while the women had the run of the house.

Just before closing time, they ensured they were the last customers at the bank, when Ned Kelly told the teller they would like to make a withdrawal, and the gang netted 2000-Pounds. Collecting the family of the Bank Manager, Mr. Scott, Ned Kelly apologised for any inconvenience and asked them to accompany them to Faithfull Creek. It showed good politics to appeal to the sensibilities of Mrs. Scott in this matter, who assured there would be no trouble. The family, tellers and two serving girls were loaded into two wagons; one of the serving girls identified Steve Hart, having gone to school with him. On the way to the outlying station they passed a procession of townspeople returning from a funeral. Respectfully, the Kelly entourage tipped their hats, and the unaware townsfolk returned the courtesy.

At Faithfull Creek, one brave man demanded to know what had happened to the women and children. Joe Byrne, who had remained on guard at the property, assured them the women were unattended at the house, to which Dan Kelly joked that he would like to be able to attend them. Said within earshot of his brother the older Kelly, known and loved for his gallantry, reacted angrily and ordered his brother never to speak disrespectfully of women.

Before leaving Euroa, the Kelly Gang (as they were now known) treated their captive audience to an impressive display of trick riding; stretching across horses at full gallop and grabbing a kerchief from the ground in their teeth. Joe Byrne demonstrated his skill at shooting a hole through a sixpence thrown into the air. The gang instructed the captives to wait two hours before raising the alarm, but it was well after midnight (fully three hours later) before they awoke the local constable and delivered news of the daring raid.

In February 1879, the Kelly Gang struck again, this time at the New South Wales town of Jerilderie.

Stopping at Davidson's pub, outside town, Joe Byrne got chatting the barmaid, who unwittingly told the handsome stranger the town was protected by two policemen, constables Richards and Devine. At midnight, the gang rode to the police station, Ned Kelly rousing the policeman with the ruse that there had been a murder at Davidson's pub. Rushing to the door, the police found themselves officially bailed up and were safely ensconced in their own lock-up for the night.

The next day, Ned Kelly did chores for the pregnant Mrs. Devine and insisted on emptying the bath water, saying it was too heavy for a woman in her condition. On Sunday morning, Dan Kelly helped the policeman's wife to prepare the local hall for Mass and accompanied her to the service. On Monday they donned police uniforms, posing as reinforcements to protect against the Kelly Gang. Entering the Bank of New South Wales, they bailed up the astonished tellers but were told the keys to the safe were with the manager, Mr. Tarleton. Ned Kelly finally found the bank manager in his bath and patiently waited for him to get dressed so the robbery of 2000-Pounds could be completed. Joe Byrne delighted in taking the papers held over the farms of struggling settlers and burning them in a bonfire out the back. Meanwhile, Dan Kelly and Steve Hart were entertaining townspeople in the hotel next door. When Ned Kelly arrived, a clergyman stepped forward and bravely told the outlaw leader that Steve Hart had stolen his watch, a timepiece of sentimental value. Ned Kelly immediately demanded that Steve return the watch.

The crowd asked Ned Kelly to tell their story and, in the now flowing tones of an experienced orator, he relayed the course that had led them to outlawry, and his concerns about what he felt was the persecution of poor people and the disadvantaged by a police force that, at the time, was rife with corruption and comprised of recruits that included ex convicts. So spellbound was the crowd that they didn't hear two men enter the hotel. One was a local businessman who was grabbed by Dan Kelly and Steve Hart. The other was the newspaperman, Gill, who jumped the back wall and ran out of town down a dry creek bed. It was a blow for Ned Kelly, who had hoped to have a manuscript published by the newspaper. One of the bank tellers offered to take it and deliver it the publisher later. Ned Kelly agreed. The manuscript didn't make it to the publisher; the teller gave it to the police instead. Over 7000 words long, it became known as the Jerilderie Letter and one of the most exciting pieces of Australian colonial literature. In it, Ned Kelly recounted their story, made a case for police persecution and corruption, and interjected passionate passages on Irish history. Written by a young man hiding in caves, with a price on his head, it pulsated indignation and dared to challenge the authorities who deemed him a criminal.

For the next year the Kelly Gang easily avoided the clumsy attempts of police to catch them. The price on their heads had risen to a staggering 8000-Pounds, but they had an extensive network of family and sympathisers who warned them of police movements and even helped to lead police parties away from Kelly hideouts. In their outlawry, the Kellys were known to ride in and win many country racing events. Poor people of the district suddenly had money to mend fences and buy provisions, paying in sixpences and three pences, when copper farthings and pennies were more common.

Ned Kelly started the Widows and Orphans Fund of Greta, calling on police to contribute.

But, in June 1880, Ned Kelly had developed a Proclamation of the Republic of North East Victoria and set a deadly plan in motion. Joe Byrne's childhood friend, Aaron Sherritt, who had also been engaged to Joe's sister was rumored to have turned police informer. But it was not until Mrs. Byrne stumbled upon a hidden police camp watching her home, and saw Aaron in the middle of the troops, that the proof was irrefutable. Some historians say the Kellys knew that Aaron was acting as a double-agent, but a blazing row with Mrs. Byrne after the police camp incident indicates this may not have been the case. Kate Byrne also broke-off their engagement. Whatever the case, Aaron was indeed an agent the police code named Moses and they were concerned enough about him to install a four-party protection squad in his house outside Beechworth.

On the night of 26 June 1880, Aaron was at home with his new and pregnant wife Rita, her mother Mrs. Barry and the four policemen, when there was a knock at the door. A neighbour's voice said he had lost his way and Aaron was laughing when he opened the door. But the neighbour had been waylaid by Joe Byrne and Dan Kelly, and Aaron found himself facing his old friend. Joe Byrne shot Aaron Sherritt and called on the police to come out of the hut and fight. They didn't, literally taking cover under the bed and pulling Rita Sherritt and her mother to its safety, where all stayed until morning.

The outlaws left within an hour and rode to Glenrowan, a railway hamlet near Greta, where they met with Ned Kelly and Steve Hart. Ned Kelly had planned the shooting of Aaron Sherritt would bring a Special Police train from Melbourne and he was now having the tracks lifted to derail the train in an act of ultimate defiance against officialdom.

They took over the Glenrowan Inn, to which they brought key figures from the community such as the policeman, Constable Bracken. They expected the news of Aaron Sherritt's murder to be reported immediately and the police train to arrive by the early morning. They could never have anticipated that it would be fully mid morning before the police in Sherritt's hut would venture into town to raise the alarm. Further bungling in Melbourne delayed the train for the best part of another day, so it was 18 hours after the shooting before the train was even dispatched. Meanwhile, the Kellys amassed a total of 62 captives in the small hotel. To keep the crowd happy, a hooley was taking place and everyone engaged in jigs and reels, while the drink flowed freely.

By midnight on Sunday, Ned Kelly had decided to abandon the plan. They had been waiting for two days, without sleep, and constantly on guard. But, just as everyone was starting to file out of the hotel, the sound of the train was carried on the still night air. A little earlier, the school teacher Thomas Curnow had asked Ned Kelly if he might take his wife and sister home, as his wife was not feeling well. Dan Kelly didn't trust Curnow and advised Ned not to let them leave, but Ned Kelly immediately relented, advising Mrs. Curnow: “Go straight to bed and don't dream too loud”. Away from the hotel, Curnow abandoned his wife and sister and took a lamp and red scarf down the railway tracks. His warning was spotted by a pilot engine preceding the police train, and both came to halt outside the town. When Curnow told his amazing story, he was allowed to hurry away to safety, and the trains shunted slowly into Glenrowan. Police poured from the train and surrounded the hotel.

It was too late for anyone to leave. Advising the captives to lie on the floor out of harm's way, the outlaws disappeared into the back rooms, to reappear dressed in armour. They must have made an astonishing sight, clanking to the front veranda to face a barrage of police fire. In the shadow of the veranda, it was not apparent that the outlaws were wearing armour, but an odd clanging sound was

heard with every volley. The armour was visionary in its ability to protect the vital organs of the torso and helmets protected the head. But the arms and legs were unprotected and the heavy armour (95lbs) limited their manoeuvrability. The slits in the helmet also limited the field of sight.

In the first volleys, the police didn't realise they had hit the outlaws hard. Ned Kelly sustained serious injuries; a bullet passed through the forearm of his left arm and, as the arm was bent holding a rifle, exited the bicep, another bullet shattered his left elbow, one lodged at the base of his right thumb, and another entered the big toe of his right foot and exited at the heel. Joe Byrne was shot in the leg.

During the night, Ned Kelly left the inn several times, undetected by the police. He was gauging the movements of police, releasing the horses before they were shot by police and, in his last foray, he went to warn over 30 sympathisers waiting to join the uprising. Telling them the plan had gone wrong and it was now the Kellys fight, Ned Kelly ordered them to return to their homes, then went back to the inn alone to try and save his brother and mates.

Inside the inn, the publican's 13 year old son was shot by police and later died from his injuries. Her 14 year old daughter suffered a grazed forehead from a bullet. Two civilians were also shot; one died instantly and the other would die later. Several times the captives tried to leave the inn, but police fire forced them back, their screams and pleas ignored.

Inside the inn, Dan and Steve were becoming despondent. In an effort to cheer them, Joe Byrne poured a drink and toasted, “Here's to the bold Kelly Gang. Long may they live in the bush”. At that moment, a police bullet thwacked through the wall and hit him in the groin. In his 23rd year, Joe Byrne fell and bled to death on the bar room floor.

On his way back to the inn, Ned Kelly tried to reload his rifle but his left arm was hanging useless and he had to abandon the task. Loss of blood, lack of sleep and the weight of the armour overcame him and he passed out. He awoke to the sound of muffled voices, as two policemen passed within 10 feet of where he was lying. Lurching to his feet, he painfully reloaded his revolver. The green skullcap his sisters had made to protect his head from the helmet fell to the ground, blood soaked. He pulled on his helmet and, with a superhuman effort, he made his way to the hotel, coming on police from behind.

He made an eerie sight as he came through the winter morning mists, brandishing his revolver, his coat flapping in the breeze. At first nobody knew what it was. One newspaper man said it was “like the bunyip descending upon us”. There was an uncertain silence, during which the iron clad figure thumped its chest with a dull ringing sound and taunted, “You can't hurt me, I'm made of iron”. When the spell was broken, 50 police opened fire. The huge figure staggered under the impact, but continued to advance, firing wildly. At one point, he even sank to one knee, but still nobody rushed him and he regained his footing to lurch forward. It was only after a particularly strong volley that made him stagger and he parted his massive legs to steady himself, that one policeman saw a gap in the armour and fired. Hit in the hip, Ned Kelly toppled like a fallen tree and police converged on the prone figure. One policeman wrenched the revolver from his hand, the muffled voice heard to grumble: “Break my fingers”. Ripping the helmet from his head they gasped to see it was the outlaw leader. One grabbed him by the beard and rammed a revolver in his face, threatening to kill him. Another kicked him in the groin. “Cowardly to kick a man when he's down,” Kelly said.

Ned Kelly was taken to the railway shed where a doctor tended his wounds. He was found to have 28 shots, five of them serious. His body was also severely bruised. He was so close to death that a Catholic priest was called to give the prisoner the Last Rites. But, despite his condition, Ned Kelly lucidly answered a barrage of police questions. By now, a crowd had gathered at Glenrowan, including members of the Kelly family. A police cannon had been ordered from Melbourne and troopers were heaping straw against the side of the inn. Police demanded that Ned Kelly ask his brother and mates to surrender, but he refused. The Catholic priest, Fr. Gibney, asked if he could go to the hotel and Ned Kelly told him no. “But surely they wouldn't shoot a priest?” he said. “They won't know who you are and they won't wait to find out,” the outlaw responded.

Outside, his sister Maggie Skillion was told by police to ask her brother to surrender. She refused, but had to be restrained as she tried to run screaming to the hotel when the straw was set alight. Ignoring police orders, Fr. Gibney also ran to the hotel, crucifix aloft, calling: “I'm a Catholic priest, I've come to help you”. When he entered the building, it was already well alight and dense smoke made visibility poor. In the bar he found Joe Byrne and realised he was dead. In the kitchen he found mortally wounded civilian Martin Cherry. Hefting the man onto his back, he ran from the hotel, passing a room as he did, he saw Dan Kelly and Steve Hart lying seemingly unconscious. Calling to police there was no threat, Fr. Gibney knew there was time to get all out of the hotel. However, at the last moment, Joe Byrne's already singed body was pulled from the inferno. Horrified onlookers could only watch as the flames engulfed the building and the blazing roof fell on the prone figures of the young outlaws.

From the ruins, the charred remains were raked from the ashes and placed on bark sheets. Grotesque and unidentifiable, one had the stump of an arm raised as if eerily pointing at something. The Kelly girls were led to the gruesome sight, where newspaper reports say they uttered dirge-like cries and wept bitterly. The bodies of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart were taken by family and sympathisers back to the Eleven Mile Creek where an Irish wake was held. Police, realising they shouldn't have allowed the bodies to be taken, showed up to reclaim them but were told that 100 men mad with grief were heavily armed and prepared to protect their dead. Wisely, the police retreated and 19 year old Dan Kelly and 20 year old Steve Hart were quietly buried in Greta Cemetery the next day.

Joe Byrne's body was taken to Benalla and kept in the lock-up overnight. The next morning it was strung-up against the cell doors, for morbid sightseers to pose for photographs with the body, before a young woman burst from the crowd and threw her arms around it crying: “Can't you give Joe Byrne peace at last?” At midnight, Joe Byrne was buried outside the confines of the Benalla Cemetery, as was custom with criminals. Only a policeman and undertaker were in attendance.

Surviving the night, Ned Kelly was also taken to Benalla and transported to Melbourne for convalescence. Returned to Beechworth some months later for a preliminary hearing, unable to stand and having to wear slippers on his wounded feet. He was again transported to Melbourne, where feeling was thought to be less pro-Kelly. In the train he gazed out at his beloved North East, already known as Kelly Country.

At the Melbourne Gaol, he was reunited with his mother who still had a year on her sentence. Stooped and frail from scrubbing flagstones, Ellen had heard little about her sons during her imprisonment. Now she knew that her youngest son was dead and her oldest was awaiting trial for murder. It was a sad and emotional reunion for mother and son, the details of which were never disclosed by the Gaol Governor.

In November, Ned appeared before Justice Redmond Barry at Melbourne Supreme Court. He was formally charged with the murder of Constable Lonigan at Stringybark Creek. The trial, the transcripts today branded a farce by leading Melbourne lawyers, was swift. Most of the witnesses were members of the constabulary. It took just two days for the trial proceedings to be completed and jury deliberated for only 30 minutes before returning a guilty verdict. When Justice Barry started to pass sentence of death, one of the most amazing discourses in Australian legal history began between the Supreme Court Judge and the prisoner at the bar. At its end, Ned Kelly said: “A day will come at a higher court than this when we shall see who is right and who is wrong” before the judge passed the sentence of death by hanging. When he had finished Ned Kelly said: “I will add something to that. I will see you where I am going”.

A petition for clemency was signed by 60,000 people, massive public rallies were held and, at 16, Kate Kelly fell on her knees before the Victorian Governor LaTrobe to beg for her brother's life. But it was all to no avail.

Ned Kelly wrote his last letter:

“I do not pretend I have lived a blameless life … nor that one fault justifies another but the public, judging a case like mine, should remember that even the darkest life may have a bright side.

“After the worse has been said against a man … he may, if he's heard, tell a story in his own rough way that would lead them to soften their harshest thoughts, and find as many excuses for him as he would find himself.

“I know, from the stories I have been told, that the press has not treated me with the kindness often afforded a man awaiting death...

“Let the hand of the law strike me down if it will. But I ask that my story be heard … people in the cities do not know how the Police in the country abuse their powers … if my lips teach the public that men are made mad by bad treatment, then my life will not entirely have been in vain.”

At 10am on Tuesday 11 November 1880, Ned Kelly was hanged at the Melbourne Gaol, with the immortal last words: “Such is life”. He was just 25 years of age. Two days after Ned Kelly's execution, Justice Redmond Barry fell ill from complications of diabetes. Despite the best medical care, he died nine days after the outlaw who said: “I will see you where I am going”.

Six months after Ned Kelly's death, a Royal Commission was held into the actions of the Victorian Police. In testament to Ned Kelly's accusations of persistent police corruption, especially towards the poor and disadvantaged, over 250 police from the rank of Police Commissioner down were demoted, dismissed or pensioned-off; representing one-quarter of a force numbering only 1100 at the time.

The police of the 1870s were a taxed commodity, made up largely of raw recruits that often included ex convicts. In a misguided effort to keep the peace, they had an official "pounce and put away" policy in which they would target struggling settlers, particularly those with large numbers of youth, and nab them even before they had done anything, with the idea that they'd be too scared to offend. Of course, it didn't work and the Irish, with their large families, were often the targets.

Police, particularly in country areas where they were far from the base of power, were also too often known to get involved in such skullduggery as breaking fences to let stock out, then round it up and take it to the pound so farmers had to pay a fine to retrieve stock that often meant their livelihood. They also had the power to veto settlers who had scraped together the deposit for a land selection that they were entitled to get through the Land Act. It was rife corruption and standover tactics.

During the Kelly Outbreak, over 50 men were arrested as suspected sympathisers - some were, some weren't and some didn't even know the Kellys. But they were all poor and they were kept imprisoned for three months, without charge. This was at crucial harvest time, so women and children had to try and bring in the crops that could mean the difference between life and death for them, or certainly whether they were able to keep their farms or not.

The seriousness of the situation was obvious, given the results of the Royal Commission after Ned Kelly's death. It may have been hard for them, but the results were ultimately good for the force, getting rid of a lot of the bad seed. It seems Ned Kelly provided a valuable social service to Victoria!

Following his death, Ned Kelly's head was decapitated so his brain could be examined to see if the brain of a criminal differed from that of an ordinary man. Examined by doctors and students, it is believed that samples of the body are included in every scientific collection at the University of Melbourne. His skull was used as a paperweight by a petty government official and his headless body was buried in an unmarked grave in the prison.

Subsequent building works resulted in the body being moved some 13 or so times and its final resting place was unknown for decades, believed to probably be in the grounds of Pentridge Prison.

In 2011, development of the decommissioned Pentridge Prison unearthed remains, one of which was identified through mitochondrial DNA testing, using a sample from Leigh Olver, a descendant of Ellen Kelly's daughter Alice King, the infant who had accompanied her mother to jail for the first year of her sentence. In November 2012, the decision was finally made to give the remains to Kelly family descendants for burial in North East Victoria.

Father Joe Walsh O.S.A from our parish, now over eighty years old and living in Villanova College Priory, Coorporoo, Old Australia, sent over paper cuttings with information on the confirmation of Ned Kelly’s remains. He has since sent newspaper clippings of Ned Kelly’ funeral, these will go on display at Ned Kelly’s, The village Inn in Moyglass.

Ned Kelly was survived by his sisters, mother and one brother. His sisters Maggie and Kate would both die young before the end of the century, although Grace Kelly lived to old age. She married

Paddy Griffiths and her descendants still live in Kelly Country, alongside Lloyd cousins. Jim Kelly never married and cared for his mother until her death in 1923. Jim died in 1947.

Ned Kelly will always be a hero to local people in Moyglass as our parents and neighbours always spoke of him as a strong man who stood up for the poor against corruption. We look on him as the Robin Hood of his day. Also the fact that we know descendants, the late Phil Kelly and Mary Fleming (nee Kelly) who were also reared in Clonbrogan makes the story more realistic for locals.

The old church (later a School), the barracks at Mobarnan and Newpark Police Station, site of Red Kelly’s house are all there to be visited and could prove big tourist attractions to Australians and others. Many local people have a good knowledge of the Ned Kelly story and chat about it regularly in the pub.

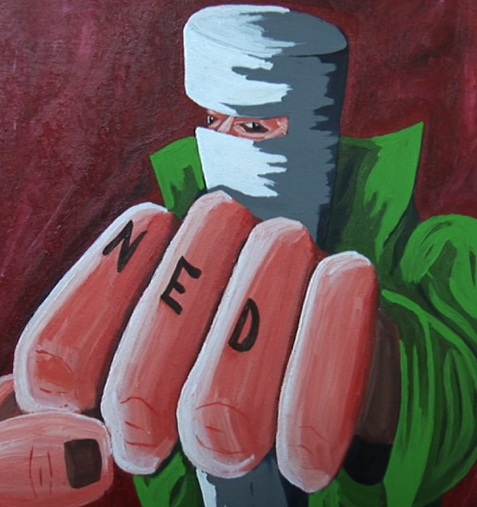

Many Australians visit the pub where there is a full history and family tree on display. Now we have created a replica of his suit of armour, which is on display in the pub and was worn by Junior Tynan at the Gathering launch at the Rock of Cashel and also in April for TG4, who filmed in Moyglass for a programme to be aired in September 2013.

RTE were in Moyglass filming on a few occasions from October 2012 to January 2013 and a half hour Nationwide programme was aired on January 16th. The identification of Ned Kelly’s remains and the Gathering 2013 initiative prompted the Nationwide programme, which also covered the story of “John Red Kelly” and visited the sites associated with him. The programme on RTE1 was well received by all and provided great publicity for the area. I sent a copy DVD to Siobhan O’ Neill in Australia, who is a close friend of the great granddaughter of John Kelly’s sister Ann. She has shown it to her fiend Dottie and is also going to travel to Kelly country to show it to other relations.

Ned Kelly was finally granted his dying wish when, 132 years after his death he was laid to rest in consecrated grounds. A funeral mass was held at St. Patrick’s church, Wangaratta on January 18th and Ned Kelly was finally laid to rest Sunday January 20th 2013 at Greta cemetery in North East Victoria. He was buried beside his mother, Ellen’s unmarked grave. His brother Dan and fellow gang member Steve Hart are also buried in Greta cemetery ,in the heart of Kelly country, a short drive from his famous last stand at Glenrowan. Monsignor John White, assisted by Fr. John Ryan and Fr. Frank Hart was the chief celebrant. Monsignor White was a fitting choice to preside as he was born in Jerilderie and a past priest at Euroa and still conducts mass at Glenrowan.

Monsignor White in his eulogy said “ This man Ned Kelly has a certain immortality” ,” not just in our hearts but in the hearts of Australia” . I think you could include Ireland and further afield in this quote.

Written by Matty Tynan in association with Siobhan O’ Neill in Australia.

Ned Kelly – John Red Kelly – Story to Date

Paintings by John Hayes - johnhayesartwork@gmail.com

The annual Ned Kelly Weekend 2013 festival was held over 9-11 August in Beechworth, Australia.

Located some 284km (176mi) north east of Melbourne, Beechworth is a beautifully preserved town of the Australian 1850s’ Gold Rush.

The town’s sandstone buildings and wide streets were also a popular haunt of the Kelly Gang in the 1870s.

Highlights of the festival include performances recreating key events in the actual place and on almost the same dates as they happened for Australia’s last and most lauded bushranger.

Two major events are the Committal Hearing of Ned Kelly and the Trial of Ellen Kelly in the Beechworth Court House.

Back on 15 April 1978, Ellen Kelly (nee Quinn) appeared in the dock, following the infamous Fitzpatrick Incident that was the catalyst for the Kelly Outbreak.

The Trial of Ellen Kelly recreates those proceedings through a narrator, character performances, and recreated transcript testimonies.

Then on 6-11 August 1880, Ned Kelly appeared in the same dock and, with the exception of a narrator, his Committal Hearing is recreated in meticulous detail,

faithfully following the proceedings as they happened.

Like his mother before him, Ned Kelly’s appearance was before Justice Redmond Barry; Cork-born of landed gentry English parents.

A host of activities also include recreations of Ned Kelly’s transport through the streets of Beechworth to and from the Court House,

and the Raid at Sebastopol centring on the police hunt for the gang; the biggest police hunt in Australian colonial history.

This year also saw the first recreation of the burning of the Glenrowan Inn, where the other members of the gang – Dan Kelly, Joe Byrne and Steve Hart

– died and Ned Kelly was captured at his famous Last Stand in June 1880.

Other attractions include demonstrations of colonial crafts, traditional firearms and cannon displays, performances and lectures about the Kellys and their time,

the Burke Museum, walking tours of historic points of interest, and tours of the (now decommissioned) Beechworth Gaol, which ensure there is plenty to interest historians

and tourists alike.

This year, hundreds of visitors again flocked to this picturesque hamlet to celebrate all things Kelly and, while dates for the Ned Kelly Weekend 2014 are still to be set.